In this article I will take an overview look at the work of Professor Stuart McGill, the McGill method for back injuries and what it means to those with chronic lower back pain.

Who is Stuart McGill?

Dr. Stuart McGill is a former professor of the the University of Waterloo, where he studied the injury and rehabilitation mechanisms of lower back pain for 30 years.

This included working with the general population, those with occupational risks and even elite athletes from around the world.

His time there produced over 245 peer-reviewed scientific papers and several textbooks on understanding and solving the problem of lower back pain.

He is now Chief Scientific Officer for his company Backfit Pro Inc.

So What is the McGill Method to Back Pain?

It depends!

With all of his studies, books and articles his approach can only be summed up with the phrase “It depends.”, by that we mean the process of solving a patient or client’s back pain problem MUST first start with a thorough assessment to understand the exact problem we are dealing with.

What is the patient’s current injury?

We must first understand what the patient’s current injury is.

Do they have a current disc bulge or herniation? Do they have sciatica? Do they have stenosis? Do they have a fracture in the spine?

What is the current mechanical state of their spine and how does the pain present itself?

Here we will take on board any current MRI, X-rays or CT scans they may have and listen to how the describe their pain and problem. We need to understand the type of pain they have, where it is and when they notice it.

Are there certain tasks or times throughout the day when they notice their pain is worse? Is there a pattern to their pain?

For example do they have good days vs bad days? Is the pain worse first thing in the morning (possibly due to instability) or worse towards the end of the day (in response to compression or aggravating movements)?

What is their injury history?

How long have they had their pain and how has it changed over time?

Have they previously had surgery, or are they contemplating it for the future?

Has their pain changed since their surgery?

We need to know how the original problem started and what has happened since then. They may have a different type or level of pain now then they did originally.

What have they already tried previously to help solve the problem? Have they tried Yoga/Pilates/Chiropractic/Osteo/Physio/pain management/surgery? What were the results?

Has anything they have tried previously helped or hindered the situation?

What triggers their pain?

Now we can really start to examine the injury and start to zero in on a precise diagnosis for the patient with pattern recognition and provocation testing.

Does the patient’s pain change throughout the course of the day? If it does, is it better in the morning or evening? Does that depend upon what they are doing?

Which postures, movements and loads provoke pain? For example does a flexed (rounded) lumbar spine provoke pain or discomfort?

Is sitting for a long period a problem? Or does standing provoke pain and sitting helps them to feel better?

Do certain day-to-day tasks provoke pain? Getting out of chair? Into and out of a car? Loading a dishwasher? Picking up their children/grandchildren?

What if they twist? or roll over in bed?

Here McGill’s provocation testing proves invaluable….

What is McGill Provocation Testing?

Provocation testing is a series of tests that subject the spine to different potentially irritating loads and postures, letting us determine the exact mechanics of the injury.

For example, the slump test routine is designed to assess flexion intolerance in a patient and also see if the patient has a live disc bulge or herniation that is compressing on the sciatic nerve root.

Some of the McGill Provocation tests and what they mean:

| Test: | What it means: |

| Slump Test | Flexion and compressed flexion intolerance. Discogenic sciatica will respond to compressed flexion. |

| Standing Extension Test | Tolerance to extension (opposite to flexion). Those with facet joint issues/stenosis or sheer force intolerance will have a reaction here. |

| Dynamic Compression Test/ Heel drop | Tolerance and stability of the joints in the spine in response to a sudden jolt, those with a unstable joints or poor spinal proprioception will have a (sometimes severe) response to this test. |

| Static Compression | Tolerance to progressive compression. Those with end plate damage will notice an increase in pain symptoms as compression increases. |

| Lateral Sheer Force | How well can the spine stabilise against lateral (sideways) forces acting on it? |

| Straight Leg Extension Test | In those with sciatica, this can help us determine if they will be suitable for nerve flossing techniques to help them alleviate pressure on the sciatic nerve root. |

Now a good practitioner will not need to run every test, but rather by gathering evidence from talking to the patient about their pain’s characteristics and injury history, they will already have an idea what to look for and will select the most appropriate tests for further clarification.

It should be noted that as much as these tests help the coach/clinician to understand the problem, they also help the patient become aware of the “rules of the game” for their back injury. After a successful testing process the patient should be better equipped to understand the aggravating posture and movement habits they currently have that keep provoking their pain and preventing recovery.

What makes them feel better?

Now that the patient has an understanding of what makes their pain worse, the next focus should be to make them aware of posture and movement habits that will help not only reduce their pain but also help the injury recover.

Part of this process will be to analyse their pain triggers and aggravators, break them down and re-learn to do any aggravating tasks in more back sparing ways.

It is useful here to think of the back as having a bank account. Pain triggers and aggravators deplete the account. When the account is low enough, pain and re-injury occurs. So how do we reduce those withdrawals and ensure we can maintain as large a bank account as possible?

For example, if the patient gets a sharp stab of pain when standing up or sitting down into a chair, how can we smooth that movement out and tune out that catch of pain? It may be that by purposely engaging a brace, that will give them enough stability to prevent the micro-movement of instability that causes that stab of pain.

But we also need to remember to treat each patient as an individual, what will work for one may make the next patient worse!

Movement strategies and exercises are just tools that we can use to help solve a patient’s back pain problem, so our job must be to select the right tools, for the right person and the right time.

Sitting and Standing Strategies to Minimise Lower Back Pain:

What are their goals?

After investigating and understanding the injury at hand, we must then begin to understand the patient. The first step in this is to understand their goals.

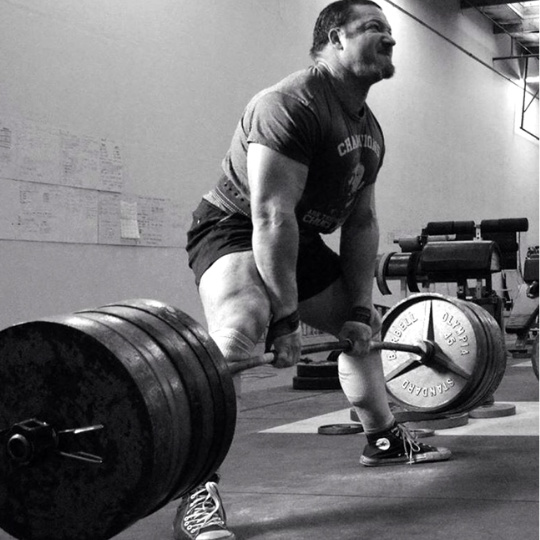

Do they just want to be pain free for day-to-day life? Are they returning to regular exercise? Or even trying to get back to the sport they love?

Knowing the patient’s will help to not only select the most useful tools to solve their problem but also allow us to steer the rehabilitation program in a direction the develops the specific skills and physical adaptations they need in order to thrive in their sport and activities.

For example, heavy barbell movements may suit someone who enjoys recreational lifting, muscular hypertrophy or powerlifting; but those tools may not suit someone looking to return to a particular sport or activity that requires a more nimble, flexible spine such as gymnastics.

By understanding the client’s goals we can fine tune spinal adaptation to best what they need to be able to do and do it well without future injury.

Summary

To summarise the McGill method, we need to take a step backwards, out of the minutia of spinal rehab and academic studies and understand first and foremost, that each patient MUST be treated as an individual.

We must first clearly understand the injury, the problem that injury presents, the patient’s goals and the patient themselves. Only once we have a clear understanding of all of these factors, can we then propose solutions and plan the best course of action going forward for that patient.

What is the McGill Method? It depends…